Lessons from the Olympics? How about a gold medal for self-delusion

Well, the main Olympics is over and I’ve enjoyed it, despite myself. I’m not a big sports fan but my youngest daughter is a keen hurdler and so I’ve drummed up enthusiasm for track and field events. Diving and cycling too — and I even got into the horse dancing. Really into the horse dancing. Don’t you go badmouthing my dancing horses.

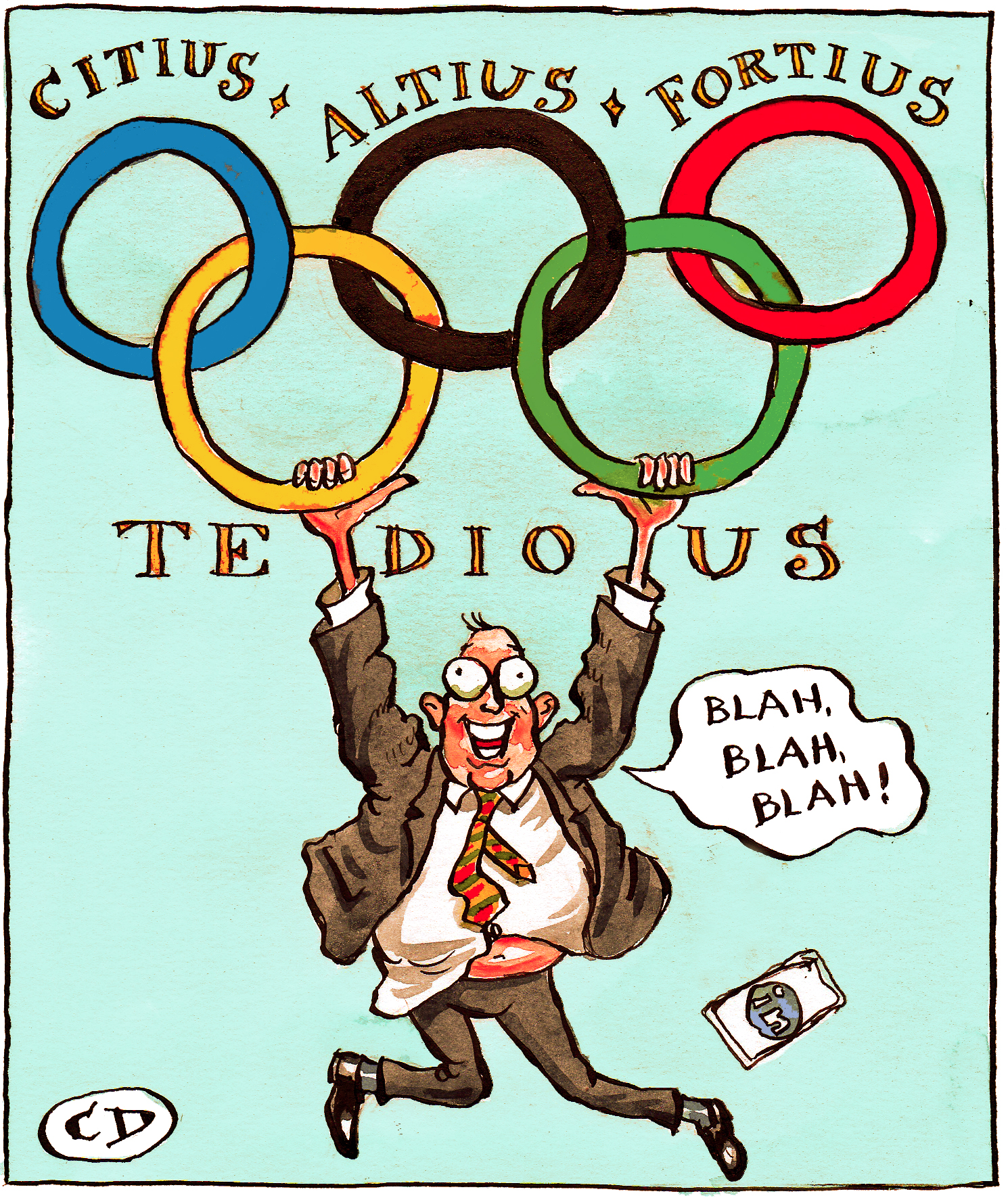

But if I’m a dabbler in Olympic fervour, my true passion is terrible business content. So for me, the real Olympic action was over on LinkedIn. My God, the takeaway lessons, the teachable moments and the insights. Every medal came with its own learnings and no discipline was too obscure to be tied to a business case. It was an Olympics of management guff. As some wit noted, every middle-aged man is posting, “I went to the Paris Olympics, here are 87 things I learnt about B2B sales.”

A quick sampling reveals untold riches: what can the Olympics teach us about strategic partnerships; what can the rail sector learn from the Olympics; Olympic athletes’ visualisation techniques; the Olympics: perseverance always pays off. I could go on forever. God knows they do.

• Olympics 2024: The over and underachievers

It’s taken as given that elite sport is chock full of business lessons, but I don’t think it is. Let’s look at the last lesson (perseverance) because it’s nonsense in so many ways. For starters, it’s demonstrably wrong: perseverance doesn’t always pay off. It improves your chances of success, sometimes. Other times, it’s just a waste of time (indeed, the perseverance of others has often wasted weeks of my time). Claiming perseverance always pays off is the sunk-cost fallacy in action.

But this is just the start. Why is the Olympics not like business? Let me count the ways.

Olympic athletes are a tiny minority of people with incredible, inborn physical talents. Like most people, I am not like them. My talents are diffuse, vague and multifaceted: I am good in some areas, average in others and below average in others, not least track and field events. My best strategy is to be above-average in half a dozen areas, just like Olympians aren’t.

In the Olympics, there is only one first place. Work often isn’t like that. Miss a sales target by 5 per cent and you’ve still got the 95 per cent; miss an Olympic gold by 5 per cent and you haven’t even got bronze. If I think of career wins, sometimes they’re obvious, but often they’re not and the route to them is full of twists and turns. Occasionally, I don’t even know what a win is or find myself shaking my head when someone tells me I’ve done brilliantly. In complex systems, there is often no magic formula and the lesson is there is no lesson.

I have just read a post about what Olympic medallists and warehouse efficiency have in common. And another about the Olympics and bouncebackability (a topic which has its own podcast). And a couple involving the mental contortions required to wring business lessons out of the Australian breakdancer Rachael Gunn, who has been accused of getting zero points on purpose. “STOP IT,” I want to scream.

For what it’s worth, I think team sports do have a bit more to teach the world of work. Because, yes, they’re about working together towards goals. But they still involve narrowly defined wins and individuals with rare and incredible talents.

In all my years of observing business, one thought I’ve had over and over and again is that the endless fixation on superlative talent is weird and that truly heroic bosses are those who get normal people to perform well (lest we forget, half of people are below average). Perhaps then, the sportspeople that companies should be looking at are non-league football teams that work well together. But why do that when you can have a shiny Olympian at your awards dinner?

OK, you might say, but you’re not an athlete. No, but even I have my thing which maps on to business achievement. I like to climb mountains. Big ones — not Everest, but up to 7,000 metres. You battle cold, altitude and exhaustion in a pursuit of a defined goal; the kind of thing that should be delivering teachable moments aplenty. But I’ve never viewed it this way. In fact, as someone who works at a desk, what I love the most about brutal physical exertion is that it’s so mindless. When I’m trudging across a glacier battling altitude sickness, I don’t think about work at all.

Also, when I look at my high-achieving friends and colleagues who have run marathons or climbed Kilimanjaro or whatever, they have always done it after the work success. It’s another string to their bow, the thing you put at the end of your CV. A piece of personal branding that says “I work hard and play hard”, not a source of business wisdom.

Back to the Olympics and I’m now reading a post about how elite athletes and chief executives have a winning mindset. Well, duh. That’s so obvious it’s not even an insight. Besides, if your insights are this trite they’re everywhere (and if they’re everywhere, they’re nowhere).

So why do it? Well, we all like to think we can distil the essence of success (and replicate it). But mainly, I suspect it’s because it’s flattering. Everyone would like to think that their job is more like Olympic triumphs and less like being an operations director. Get a gold medallist up there and a little of the glory rubs off on all of us. The medallist likes it too because corporate gigs are lucrative. People like me like it because we get to take the mickey. Everyone’s a winner except some abstract notion of truth and utility.

Still, for all my weary cynicism, I have just found a (non-Olympic) LinkedIn post which begins: “A lot of people are curious about how horses and dance can help with leadership skills.” I have to admit I’m intrigued. Perhaps stuff like this will keep me going until 2026, when we have the LinkedIn World Cup to look forward to.